Salvador Dalí worked on his painting Crucifixion (Corpus Hypercubus) for four years – this photo was taken in 1951 (Credit: Francesc Catala-Roca)īy breaking out of three dimensions, the artist could find new meaning in a traditional biblical scene, argues du Sautoy. It appears to bridge the divide that many feel separates science from religion.”

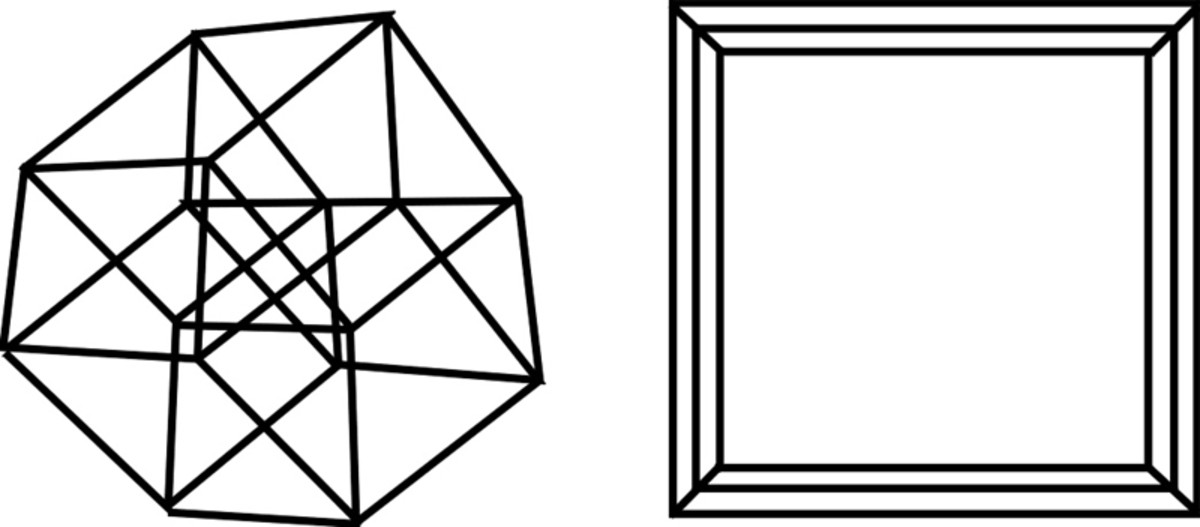

Classic 4d shapes cracked#

“The painting seems to have cracked the link between the spirituality of Christ's salvation and the materiality of geometric and physical forces. “There is a meditative intensity to Crucifixion (Corpus Hypercubus),” says art critic and poet Kelly Grovier. – Marcus du Sautoyĭalí’s own ‘sculpture of the mind’ brings geometry into the realm of the metaphysical. It’s not possible to see a 4D cube in our limited 3D universe, but there are different ways to imagine one. As he argues in his Radio 3 programme The Secret Mathematician, “It’s not possible to see a 4D cube in our limited 3D universe, but there are different ways to imagine one.”

While it’s difficult to grasp, the idea of multiple dimensions allows scientists to envisage shapes that mathematician Marcus du Sautoy calls “sculptures of the mind”. Just as the sides of a cube can be unfolded into six squares, a tesseract – or four-dimensional cube – can be unfolded into eight cubes. In a 2012 lecture given at the Dalí Museum, Banchoff explains how the artist was trying to use “something from a three-dimensional world and take it beyond… The exercise of the whole thing was to do two perspectives at once – two superimposed crosses.” Dalí’s floating cross is what Banchoff describes as “an unfolded four-dimensional cube”. It’s not even in a dimension we can see.Ĭrucifixion (Corpus Hypercubus) unites a classical portrayal of Christ with a shape that only exists in mathematical theory. Yet there are no nails in this image of crucifixion, and the cross is not made of wood. Hovering eerily in the air above a figure modelled by Dalí’s wife Gala, Jesus Christ appears in a pose that has been painted by artists for centuries. It’s not even in a dimension we can see.Īlthough Dalí continued to explore ideas of theoretical physics until his death in 1989, arguably the greatest expression of his scientific curiosity came in the form of a 1954 painting. There are no nails in this image of crucifixion, and the cross is not made of wood. He wrote in his 1958 Anti-Matter Manifesto: “In the Surrealist period I wanted to create the iconography of the interior world and the world of the marvellous, of my father Freud… Today the exterior world and that of physics, has transcended the one of psychology.

The Spanish artist had long found inspiration in science. Each year, Dalí visited New York and called on the Brown University professor for advice, setting him challenges for artworks that he hoped one day to complete – including a statue of a horse made up of three parts that were kilometres apart. When mathematician Thomas Banchoff received a message in 1975 asking him to contact Salvador Dalí, his colleague told him: “It’s either a hoax or a law suit.” Yet it turned out to be the start of a collaboration that lasted almost a decade.

By breaking out of three dimensions, Crucifixion (Corpus Hypercubus) found new meaning in a traditional biblical scene (Credit: World History Archive/Alamy Stock Photo)

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)